Vida nocturna de dinosaurios va emergiendo del estudio óptico paleontológico

Large herbivores, just like living ‘megaherbivores’, were active both day and night. Small carnivores such as Velociraptor were nocturnal hunters. Flying species, including early birds and pterosaurs were mostly day-active

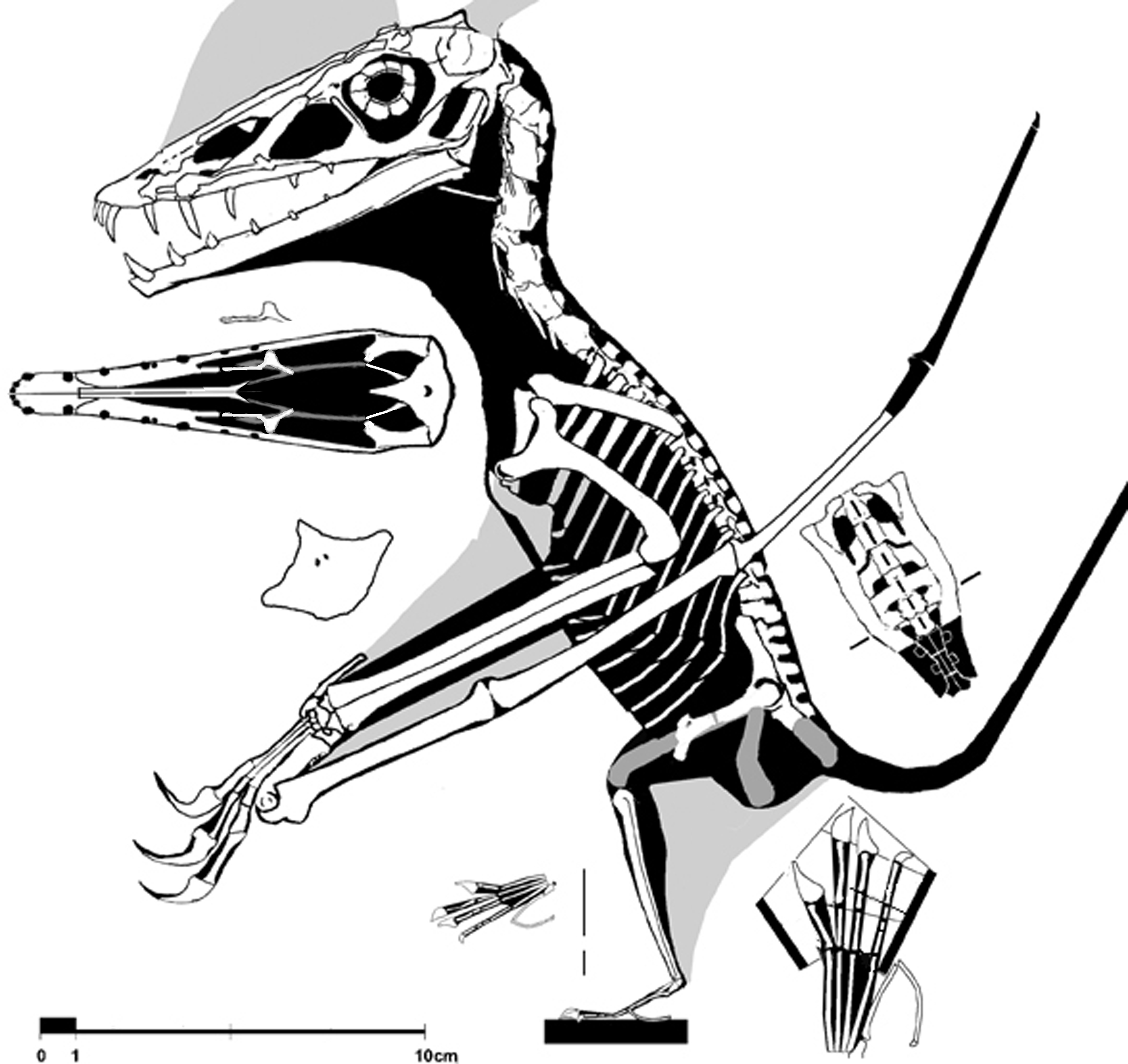

El pterosauro Scaphognathus crassirostris era un arqueosaurio diurno y volador. Su grueso anillo esclerótico ha sido destacado en azul.

Los dinosaurios también tenían vida nocturna

Una investigación estadounidense, que se publicabó en abril de 2011 en la revista Science, demuestra que algunos dinosaurios y reptiles del Mesozoico (hace unos 250 millones de años) podían ver en la oscuridad y mantenerse activos durante la noche.

Estos resultados contradicen la creencia de que estos animales sólo actuaban de día debido a restricciones energéticas. “Los ojos de estos animales nocturnos tenían una pupila muy abierta, determinada por la retina y la distancia focal, lo que los convertía en ojos con una sensibilidad a la luz muy buena”, explica a SINC Lars Schmitz, uno de los autores del estudio e investigador del departamento de Geología de la Universidad de California (EE UU).

Los investigadores analizaron la estructura del ojo de 33 arcosaurios –'reptiles dominantes', entre los que se encuentran los cocodrilos y las aves-, además de dinosaurios y pterosaurios –'lagartos alados'- de la era mesozoica. “Queríamos comprobar si es cierta la hipótesis que afirma que la mayoría de dinosaurios eran diurnos, mientras que los mamíferos eran nocturnos y vivían a la 'sombra' de los dinosaurios”, expresa Schmitz.

Los resultados, que se publican ahora en Science, demuestran que los patrones de actividad (diurno, nocturno o catemeral –activo de día y de noche-) de los arcosaurios dependían de la estructura del ojo. “Los grandes herbívoros estaban activos de día y de noche, probablemente debido a las necesidades de alimentación; los pequeños carnívoros, como el Velocirráptor (Velociraptor), eran cazadores nocturnos; y especies voladoras como los pterosaurios (a excepción de algunos como el Pterodaustro) eran, sobre todo, diurnos”, señala el investigador.

Patrones de actividad similares

Los grupos animales del Mesozoico y los de la era actual son muy diferentes: “dinosaurios vs. mamíferos, en términos sencillos”, diferencia el experto. Sin embargo, los animales extinguidos y los que hoy habitan la biosfera, como los lagartos y las aves, comparten patrones de actividad semejantes.

Los autores vinculan estas semejanzas a la ecología, es decir a la relación de los seres vivos entre sí y con el medio en el que habitan. Para reforzar sus resultados, Schmitz y sus compañeros ya han empezado a estudiar algunos de los primeros mamíferos para extender el estudio a otro tipo de dinosaurios.

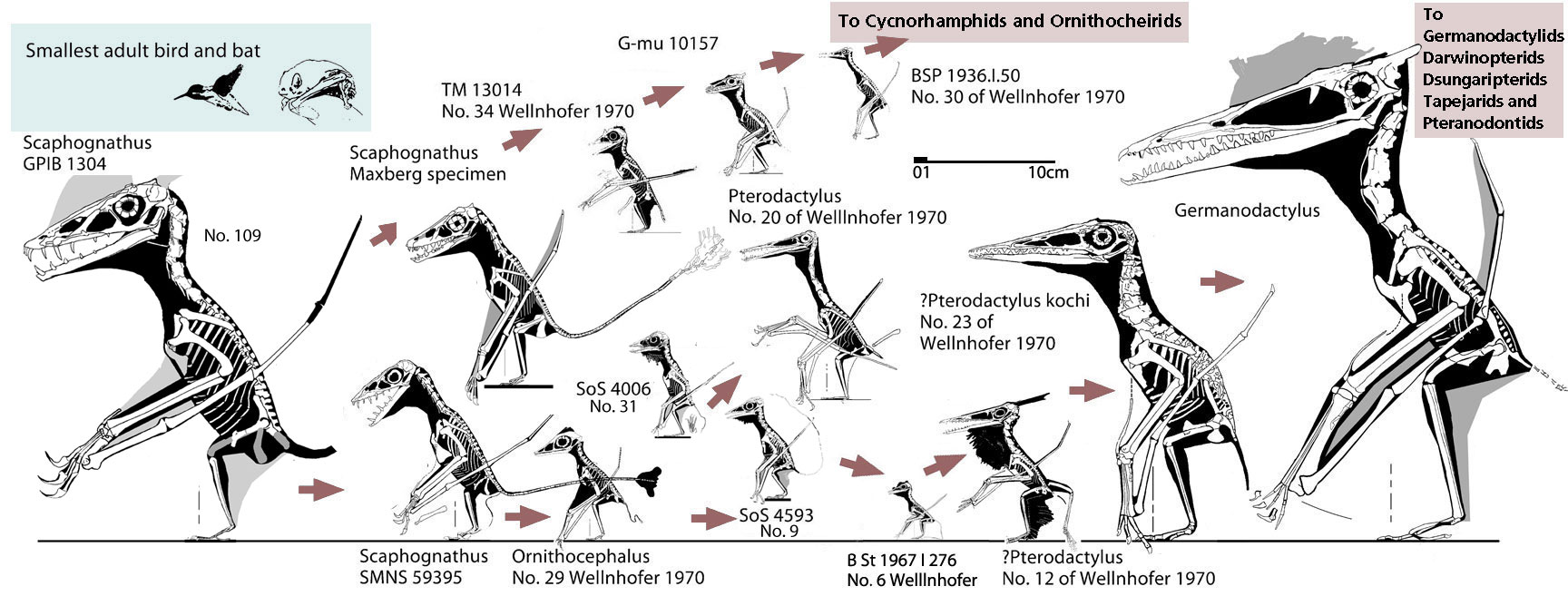

reptileevolution.com/scaphognathus.htm

reptileevolution.com/scaphognathus.htm

Scaphognathus and its descendants demonstrating the phylogenetic size reduction that drove the evolution of pterodactyloid-grade characters in derived taxa.

-------------------

Publicado por SINC el 18/04/2011 - el Servicio de Información y Noticias Científicas (SINC) nace en diciembre de 2007 para gestionar y producir contenidos informativos de actualidad científica destinados a los medios de comunicación, a la comunidad científica y a la propia ciudadanía. Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología.

Noticia publicada en El Libre Pensador (España)

Referencia bibliográfica:

Lars Schmitz, Ryosuke Motani. “Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology”. Science, 14 de abril de 2011. doi: 10.1126/science.1200043

--------------------------

Scaphognathus crassirostris 1889

From Henry Alleyne Nicholson's "Manual of palaeontology for the use of students with a general introduction on the principles of palaeontology," 1889.

Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology

Variation in daily activity patterns facilitates temporal partitioning of habitat and resources among species. Knowledge of temporal niche partitioning in paleobiological systems has been limited by the difficulty of obtaining reliable information about activity patterns from fossils. On the basis of an analysis of scleral ring and orbit morphology in 33 archosaurs, including dinosaurs and pterosaurs, we show that the eyes of Mesozoic archosaurs were adapted to all major types of diel activity (that is, nocturnal, diurnal, and cathemeral) and provide concrete evidence of temporal niche partitioning in the Mesozoic. Similar to extant amniotes, flyers were predominantly diurnal; terrestrial predators, at least partially, nocturnal; and large herbivores, cathemeral. These similarities suggest that ecology drives the evolution of diel activity patterns.

The Eyes Have It: Dinosaurs Hunted by Night

ScienceDaily (Apr. 15, 2011) — The movie Jurassic Park got one thing right: Those velociraptors hunted by night while the big plant-eaters browsed around the clock, according to a new study of the eyes of fossil animals. The study will be published online April 14 in the journal Science.

The pterosaur Scaphognathus crassirostris was a day-active, flying archosaur. Scleral ring highlighted. (Credit: Lars Schmitz/UC Davis)

The pterosaur Scaphognathus crassirostris was a day-active, flying archosaur. Scleral ring highlighted. (Credit: Lars Schmitz/UC Davis)

This conclusion overturns the conventional wisdom that dinosaurs were active by day while early mammals scurried around at night, said Ryosuke Motani, professor of geology at UC Davis and co-author of the paper.

"It was a surprise, but it makes sense," Motani said.

The research is also providing insight into how ecology influences the evolution of animal shape and form over tens of millions of years, according to Motani and collaborator Lars Schmitz, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Evolution and Ecology at UC Davis.

Motani and Schmitz, a former graduate student of Motani's, worked out the dinosaur's daily habits by studying their eyes.

Dinosaurs, lizards and birds all have a bony ring called the "scleral ring" in their eye, a structure that is lacking in mammals and crocodiles. Schmitz and Motani measured the inner and outer dimensions of this ring, plus the size of the eye socket, in 33 fossils of dinosaurs, ancestral birds and pterosaurs. They took the same measurements in 164 living species.

Day-active, or diurnal, animals have a small opening in the middle of the ring. In nocturnal animals, the opening is much larger. Cathemeral animals -- active both day and night -- tend to be in between.

The size of these features is affected by a species' environment (ecology) as well as by ancestry (phylogeny). For example, two closely related animals might have a similar eye shape even though one is active by day and the other by night: The shape of the eye is constrained by ancestry.

Schmitz and Motani wrote a computer program to separate the "ecological signal" from the "phylogenetic signal." The results of that analysis are in a separate paper published simultaneously in the journal Evolution.

By looking at 164 living species, the UC Davis team was able to confirm that eye measurements are quite accurate in predicting whether animals are active by day, by night or around the clock.

They then applied the technique to fossils from plant-eating and carnivorous dinosaurs, flying reptiles called pterosaurs, and ancestral birds.

The measurements revealed that the big plant-eating dinosaurs were active day and night, probably because they had to eat most of the time, except for the hottest hours of the day when they needed to avoid overheating. Modern megaherbivores like elephants show the same activity pattern, Motani said.

Velociraptors and other small carnivores were night hunters, Schmitz and Motani showed. They were not able to study big carnivores such as Tyrannosaurus rex, because there are no fossils with sufficiently well-preserved scleral rings.

Flying creatures, including early birds and pterosaurs, were mostly day-active, although some of the pterosaurs -- including a filter-feeding animal that probably lived rather like a duck, and a fish-eating pterosaur -- were apparently night-active.

The ability to separate out the effects of ancestry gives researchers a new tool to understand how animals lived in their environment and how changes in the environment influenced their evolution over millions of years, Motani said.

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Germany) to Schmitz.

--

Nocturnal dinosaurs

wainwrightlab.wordpress.com/.../

We make several important points in these papers:

(i) Dinosaurs were not restricted to day-activity (diurnality) by any means,

(ii) Activity patterns evolve following ecological characteristics (e.g., diet+body size, terrestrial or flying),

(iii) Physics of the environment drive the evolution of shape,

(iv) We have a great new tool for reconstructing ecology of extinct species.

So, why did everyone think that dinosaurs were diurnal in the first place? We think there are at least two (historical) reasons. First, several decades ago dinosaurs were portrayed as sluggish, “cold-blooded” animals. It seemed too unlikely that these animals were capable of being active at night, when ambient temperatures were cold compared to the day. Second, the idea of diurnal dinosaurs may have arisen because many (paleo)biologists were trying to explain why the majority of mammals is nocturnal – and the picture of dinosaurs occupying the diurnal niche, pushing the mammals into the dark just seemed to fit all too well.

Well, that story isn’t all that simple and straight-forward anymore. Dinosaurs were nocturnal, too. And we don’t even know if the earliest mammals were actually nocturnal (Kenneth Angielczyk at the Field Museum and I are working on this right now). So, the assumed split in activity pattern between mammals and dinosaurs is certainly rejected. However, we do see a different pattern emerging. It appears as if the evolution of activity patterns is driven by ecology.

We found striking similarities between the Mesozoic and today’s biosphere. Large herbivores, just like living ‘megaherbivores’, were active both day and night, probably because of foraging needs (they just had to eat most of the time…), except for the hottest hours of the day when there was risk of overheating. Small carnivores such as Velociraptor were nocturnal hunters. Flying species, including early birds and pterosaurs (like Scaphognathus above, with scleral ring highlighted in blue color) were mostly day-active (although some of the pterosaurs were actually nocturnal). These ecological patterns are also found among today’s living mammals, lizards, and birds.

So, how can we tell? Eye shape is the key. Nocturnal animals roam around in low light during the night, and their eyes show characteristics that relate to improved light sensitivity. Eye soft-tissues rarely if ever fossilize, but many vertebrates (e.g., teleost fish, lizards, and birds) have an extra bone element within their eyes, the so called scleral ring. Notably, neither mammals, crocodiles, nor snakes have scleral rings [for more details I would refer you to the work of Tamara Franz-Odendaal]. The scleral ring, however, is present in basal archosaurs, pterosaurs, and dinosaurs, which enables us to reconstruct eye shape in these fossils..

If you look at a bird eye (photos below) you will see the pupil opening defined by the iris. The scleral ring, situated within the sclera, the ‘leathery’ layer of the eye, surrounds the iris. The shape of the scleral ring and eye socket closely reflects eye shape, enabling us to distinguish nocturnal and diurnal dinosaurs.

For example, if you compare the scleral rings below, the nocturnal species on the right, a potoo, has a much larger ‘aperture’, or inner diameter than the diurnal hawk compared to eye socket size. Of course, the differences are often more subtle, so we use a Discriminant Analysis (DA) to retrieve a quantitative prediction. Prediction from a DA are rarely perfect, but overall the DA performs very well.

The relation between form and function of the eye is another convincing example how physics of the environment, that is light levels, drive the evolution of shape. However, it is not just physics that influences the evolution of shape. Shared ancestry is an important factor that may blur the form-function relation. Simply put, closely related species are expected to be more similar to each other than more distantly related species, so shape alone could potentially be misleading. With Ryosuke leading this part of the study, we solved this issue and developed a new method (implemented in ‘R’) that makes it possible to account for this phylogenetic bias. A step-by-step guide to this analysis is provided in the Supplementary Information of the paper in Science (www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/science.1200043/DC1). We hope that this method will be helpful for other studies dealing with inferences of ecology from shape.